With the heat soaring in many parts of the country one of the big questions from owners is, should I use electrolytes? With many opinions it can be confusing and leave more questions than answers. So, in order to help tackle some of these questions let’s take an in-depth look at electrolytes, what they are, what they do and how should they be used.

In simple terms electrolytes are minerals that when in their solid form bond readily with salts but when they are dissolved in water, breakdown into their component elements called Ions.

Some Ions have a + (Calcium, Potassium, Sodium, Magnesium) or – (Chloride, Bicarbonate, Phosphate) charge. These charges allow the conduction of electricity. The electrical charges carry vital signals across cell membranes and along nerve and muscle cells enabling functions such as:

• Muscle contractions (including the heart and smooth muscle of the digestive system)

• Blood volume control

• Regulation of thirst

• Absorption of nutrients

• Body fluid balance

• Production of bodily secretions such as saliva, sweat, urine, mucus, digestive fluids

So, electrolytes maintain physiological balance in the horse’s body. If there happens to be an imbalance or a depletion of electrolyte levels, then processes are severely disrupted, and potentially life-threatening changes can occur. Electrolytes need to be provided in the diet as the horse cannot produce them.

Sweat contains electrolytes and so when a horse sweats he will lose electrolytes. Horse sweat is considered hypertonic, which means a greater concentration of electrolytes exists in sweat than in fluids circulating within the body which is why losses are a concern (KER, 2004). Interestingly human sweat is hypotonic, which means a higher concentration of electrolytes remains in the circulating fluids.

Although this may make sweating sound like a concern, sweating is a vital tool in helping the horse to stay cool.

Exercise requires energy and utilization of this energy produces heat, in fact 70-80% of the energy consumed by a horse is lost as heat (Marlin 2021). As exercise demands increase there is a greater utilization of energy, and therefore heat production increases. In fact, muscles of exercising horses generate enough heat that they can increase the horses core body temperature by as much as 1.8°F per minute. If a horse was unable to remove all this heat overheating would occur in less than 10 minutes (Marlin, 2021).

Heavy work can result in excessive electrolyte losses.

55-70% of heat generated by exercise is lost through sweating (evaporation) and 25% by exhalation and the rest through convection. Sweating in average ambient temperatures allows for fast evaporation and thus cooling of the horse. However, in humid conditions the ability to remove heat through evaporation and the respiratory tract is reduced, and convection only works if the horse’s body temperature is lower than the ambient temperature. So, in hot weather, with high humidity, the ability to dissipate body heat is reduced resulting in a body temperature increase which could lead to heat stress.

Horses can lose around 4-15 litres of sweat an hour (depending on factors such as environmental temps, how hard the horse is working and how fit the horse is). A 1100 lb horse consists of around 300 litres (80 gallons) of a water (both extracellular and intercellular) and so for example a loss of 10 litres (2 gallons) per hour during exercise would be a loss of around 3% of total body water per hour (Marlin, 2021).

Some studies have indicated that even a 1% loss of hydration can lead to a 4% fall in performance, however it does appear that horse tolerate loss of hydration well and it seems to be that performance is only more drastically affected at a loss of 5% or higher. Reduction in performance is not only due to the water loss but because of the large quantity of electrolytes (especially sodium and chloride) that are lost in horse sweat. Losing 10 litres (2 gallons) of sweat is the equivalent to loosing 110 g of electrolytes (Marlin, 2021).

In order to ensure adequate hydration its worth considering how you provide your horse’s water.

Studies have shown that water consumption varies according to how the water is given, for example when small automatic drinkers were used horses drank less compared with buckets and bigger troughs (Marlin, 2020).

Temperature also seems to play a role on how much a horse will drink. For example, in colder weather ponies drank 40% more water when the water was heated (18°c). But only if that was the sole source of water available. If there was icy water (0-3°c) available as well as warm, they drank almost exclusively from the icy water but drank much less.

Ponds can be a good source of water as long as they are clean and the bottom is not sandy.

A study on working horses by Butudom et al. 2004 showed that over the whole hour after exercise horses drank the most water when at 68°F (5.2 gallons drank) compared to 86°F (4.2 gallons) or 50°F (3.9 gallons). Therefore, ideally water presented to horses after exercise should be around 59-68°F, thus if you are providing buckets, they should be monitored in hot weather to ensure they don’t become too hot. Another reason for allowing horses to drink cool rather than warmer water, is that you’ll further help lower his body temperature.

Both soaking and steaming hays are good ways to get even more water into your horse. The amount of water that will be taken up will of course depend on the water content and maturity of the forage before being steamed or soaked. Earing et al (2013) found that steaming increased the water content of alfalfa-orchard grass mixed hay from 8% to 23%. In a 2h feeding period horses also ate 4 x more steamed hay than unstreamed. Similar hays when soaked (for 15-60mins) increased the water content from 9% to 17-21%. However, soaked hay does have the down side of a small amount of nutrient loss whereas steaming does not.

The electrolytes that we tend to focus on are Calcium, Potassium, Sodium, Chloride and Magnesium.

Sodium and chloride - These electrolytes are lost in the greatest amount in sweat. When sodium and chloride combine, they produce sodium chloride. Sodium chloride is also known as table salt.

Sodium is often considered the principle electrolyte as it’s the main regulator of thirst.

Regular table salt is an excellent source of sodium and chloride.

The thirst response in horses is a physiological prompt to drink to prevent dehydration and under normal circumstances is dependent for the most part on electrolyte balance. In cases of light water loss (such as water in feces, urine, exhalation a light sweating), water is released but the level of electrolytes lost is minimal leading to a higher concentration of sodium within the blood. This causes the body to seek out water to replace the loss, and thus the horses thirst response is triggered, and water is received.

However, when the horse sweats heavily and/or for long periods of time water and sodium are both lost and thus the sodium concentration in the blood is not so large and the horses thirst mechanism is effectively turned off. Therefore, some performance horses will not drink even though they are dehydrated.

Potassium - Healthy horses require potassium for muscle contraction and relaxation. During the muscle contraction phase, potassium leaks out of the muscle cell and is one reason that if blood is taken from horses recently suffering from severe tying-up high blood potassium levels may be found.

Magnesium - Vital component of body fluids and can assist in muscle relaxation.

Calcium - Essential for normal muscle function.

Electrolytes need to be provided in a well-balanced fashion as they work side by side. For example, movement of sodium across the nerve cell membrane is necessary for transmission of nerve impulses along nerve fibers. This in turn causes the release of calcium ions that are necessary for muscle contraction and then later, magnesium is needed for muscles to relax and so you can see how a balance of electrolytes is needed in order to assist in multiple functions.

The simple answer to this is both.

The key to a good supplementation program is to first provide a balanced diet comprising of correct amounts of forage and/or concentrates along with enough salt to meet the horse’s base sodium and chloride needs. Once this is in place if a horse is working harder or sweating due to environmental conditions for prolonged periods an electrolyte can also be added.

Horses cannot rehydrate just by drinking water alone, without electrolytes from feed and/or additional supplements the body cannot hold on to the water they drink and thus forage and feed need to be provided to ensure balance within the body.

The NRC (National Research Council) indicates that a 1100lb horse in no work (maintenance) requires 10g sodium, 40g chloride and 14g potassium per day.

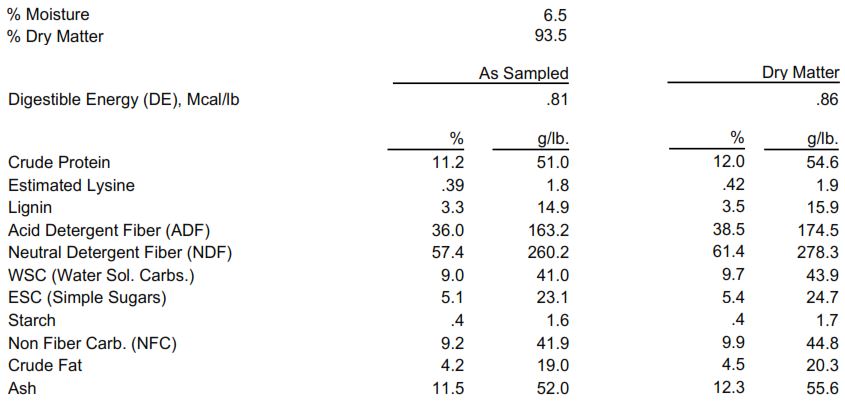

If we have a look at the common feed stuffs, it’s clear that some supplemental electrolytes may be needed. For example, in forage, which should be the basis of every horse’s diet, levels of potassium are generally good with some hays containing around 1.75-2.5% which would be enough to cover the horse’s daily maintenance needs. However, they can be low (0.05-0.5%) in sodium and chloride (0.5-0.75%). Therefore, even if a 1100Lb horse ate 2% of its body weight per day and nothing else, he would only get around 5g of sodium.

Therefore, even just to meet maintenance sodium and chloride requirements horses must have access to a source of supplemental salt.

Feeding 2 tablespoons of table salt a day will meet an average horse's maintenance sodium needs.

When horses are in work their needs increase and the level of sodium increases to 17.8g and 53.3g of chloride per day for a 1100lb horse in medium level work. Environmental temperatures, individual variances in digestion, digestibility of feedstuffs all effect the amount needing to be consumed.

Regular table salt is approximately 61% chloride and 39% sodium and so 30g (approx. 2 tablespoons) of salt per day would be enough to provide 11.7g of sodium which would cover maintenance needs.

If the weather is causing the horse to sweat just standing around or he is working moderately hard then increasing the table salt to 4 tablespoons per day should be adequate.

Horses in higher levels of work are often fed fortified grains/concentrates and while these contain some salt it is not generally enough to meet the higher demands of the hard-working horse. For those horses working hard and/or sweating heavily for prolonged periods electrolyte supplementation is needed alongside their daily salt provision.

While salt can be provided via a salt block not all horses will utilise them enough to cover the specific amounts needed. Some horse may also over consume which is not ideal. Blocks are also hard to monitor and so for performance horses especially its advisable to add a measured amount while still making a block available.

When looking for a suitable electrolyte supplement be careful to check the ingredient labels. The first ingredient in many commercial products is dextrose or sugar. These products will not have sufficient levels of electrolytes to meet the horse’s needs. Ideally there should be at least 45% chloride and the sodium: potassium: chloride ratio should be similar to sweat at 2:1:3.8.

Electrolyte supplementation should be considered well in advance of competitions as increasing electrolytes in order to effectively “load” before competition is not worthwhile. If your horse has been on regular supplementation increasing suddenly will likely a) put the horse off its food/water at a time when it most needs it b) could cause digestive disturbances such as loose droppings and c) increase the amount that is excreted. If the horse isn’t losing the additional extras his body won’t use it. Rather wait until the workload, and rate of sweating increases to provide the extra such as during the competition.

Gatorade is not a strong enough electrolyte for horses but it may encourage drinking.

The same applies for horses not on electrolytes, adding them before competition won’t fix months of under supply and so rather assess your horse's diet well in advance to ensure that you are providing what is needed. A horse starting competition on depleted levels is more at risk of issues during competition.

The best way to provide electrolytes is in feed. Electrolytes can be given in water, but the volume the horse will readily consume will not allow a large electrolyte intake. Giving electrolytes in water should be a way of rehydrating the horse, not as a way of replenishing lost electrolytes. Human sport drinks such as Gatorade do not contain adequate electrolytes for horses. Their best use is for encouraging horses to drink, NOT for electrolyte replenishment. If electrolytes are placed in water be sure to always provide a separate bucket of plain water as well.

Replacement of lost electrolytes should come through diet and/or pastes as this encourages greater intake. Therefore, it’s important to note that full replacement of electrolytes can take several days. For example, a horse running a 120km endurance race could lose 500g of electrolytes. Replacing at an amount of 100g per day would thus take 5days for full replenishment after competition. Therefore, it is important that electrolytes be provide daily during and the days that follow hard work and not just during competition.

Holbrook TC, Simmons RD, Payton ME, MacAllister CG. (2005) Effect of repeated oral administration of hypertonic electrolyte solution on equine gastric mucosa. Equine Vet Journal. Nov:37(6):501-504

Earing, J.E, M.R. Hathaway, C.C Sheaffer, B.P. Hetchler, L.D. Jacobson, J.C. Paulson and K.L. Martinson. (2013). The effect of hay steaming on forage nutritive values and dry matter intake by horses. Journal of Animal Science 91: 5813-5820

KER, 2004 https://ker.com/equinews/pass-the-salt-endurance-horses-and-electrolytes/

Kristula, M.A.; McDonnell, S.M. (1994) Drinking water temperature affects consumption of water during cold weather in ponies. Applied Animal Behaviour Science 41: 155-160.

Martinson, K., Jung. H., and Sheaffer,C. (2011) The effect of soaking on carbohydrate removal and dry matter loss in Orchardgrass and Alfalfa Hays. Journal of Equine Veterinary Science, Volume 32, Issue 6, 332-338

McDonnell, S.M.; Kristula, M.A. (1996) No effect of drinking water temperature on consumption of water during hot summer weather in ponies. Applied Animal Behaviour Science 49: 149-163.

Marlin., D (2019) www.davidmarlin.co.uk and Social media postings relating to the work done

Marlin, D (2020) https://drdavidmarlin.com/hydration-forage-hay-soaking/

David Marlin Electrolyte Webinar, 2021 https://drdavidmarlin.com/electrolytes-for-horses-never-be-confused-again-dr-david-marlin/

D., Marlin., Misheff., M., Whitehead., P (2018) Optimising Performance in a challenging climate preparation for and management of horses and athletes during equestrian events held in thermally challenging environments

Forage

Forage should be the foundation of every equine diet and should be carefully selected to cover as much of the horse’s daily requirements for energy, protein and fiber before a concentrate is even considered.

Forage should be the foundation of every equine diet and should be carefully selected to cover as much of the horse’s daily requirements for energy, protein and fiber before a concentrate is even considered.

Fiber is an energy source that is often overlooked. Digestible fibers (cellulose and hemicellulose within the plant) are broken down by the microbial population in the horse’s hindgut into volatile fatty acids (VFAs) these are then used for energy or stored in the form of fat or glycogen. A portion of indigestible fiber (lignin) is included within the plant but is not useable by the horse. Lignin content increases with maturity and so the more mature a grass/hay is, the less digestible it will be, highlighting the need for careful selection of forages.

A constant forage supply is necessary to keep the microbial population of the gastrointestinal tract working optimally. Limiting or removing forage can result in issues such as colic and gastric ulcers. The average horse will require at least 1.5% of body weight in forage per day. Easy keepers may need a lower percentage where as hard keepers and those in higher demand life stages (such as a lactating mare) may require significantly more.

Forage Types

Forage includes many sources such as pasture, hay (grass and legume) and processed forages. A selection of forage types are available but most commonly horse owners rely on two:

Other forms of forage include processed forages. These include hay cubes, pellets, chaffs, compressed hay flakes/chunks, soy hulls and beet pulp.  These forage alternatives can help stretch supplies of hay, especially during winter months when additional amounts are being provided in order to help keep horses warm while maintaining condition and can dwindle faster than anticipated. Having a small amount in the diet on a regular basis enables you to increase quickly without having to introduce something new, and so keep this in mind before going into seasons where hay availability may become an issue.

These forage alternatives can help stretch supplies of hay, especially during winter months when additional amounts are being provided in order to help keep horses warm while maintaining condition and can dwindle faster than anticipated. Having a small amount in the diet on a regular basis enables you to increase quickly without having to introduce something new, and so keep this in mind before going into seasons where hay availability may become an issue.

Some chaffs and pellets may even contain a flavoring which will help tempt fussy eaters but watch out for heavily molassed products if you have a horse with issues such as Laminitis, or Cushing’s where sugars need to be monitored.

Dried grass products can be higher in sugars and some products contain added sugars and/or additional grains to increase the energy density of a product. Contact your chosen brand for more information if this is a concern for your horse. Remember that NSC includes sugar and starch, and so even though a product may be advertised as “low sugar” it may still have a high starch content making it unsuitable for some and so be sure to look at the total NSC.

Forage Alternatives

Currently there is no standard marketing for manufactured fiber products and so whether the marketing notes them as a replacer, stretcher or extender they are there to do the same job, to provide additional fiber in the diet.

Fiber is a term referring to a collection of carbohydrates such as cellulose, pectin, and lignin, these fractions exist in pellets, cubes, chaffs just as they do in hay and so it is possible to meet the horse’s fiber need from pellets alone, but not all pellets/cubes are created equal.

When choosing a forage alternative be sure to look at the crude fiber content and check the ingredients list to ensure that it contains mostly hay. Some cubes can have added ingredients such as grain and thus the fiber portion of these types could be reduced to where it isn’t adequate. Cubes that are mostly hay will have a crude fibre content within the 20-30% range. That being said some complete feeds which may contain levels as low as 18% fiber can still be used as the sole diet as they will also contain additional vitamins and minerals. Another factor to consider is the digestibility of the ingredients included in a forage alternative. For example, alfalfa, timothy hay and soy hulls are highly digestible, whereas rice hulls and peanut hulls will increase the crude fiber value on the label but they are poorly digested by the horse and thus the horse will not gain the same benefit.

When choosing a forage alternative be sure to look at the crude fiber content and check the ingredients list to ensure that it contains mostly hay. Some cubes can have added ingredients such as grain and thus the fiber portion of these types could be reduced to where it isn’t adequate. Cubes that are mostly hay will have a crude fibre content within the 20-30% range. That being said some complete feeds which may contain levels as low as 18% fiber can still be used as the sole diet as they will also contain additional vitamins and minerals. Another factor to consider is the digestibility of the ingredients included in a forage alternative. For example, alfalfa, timothy hay and soy hulls are highly digestible, whereas rice hulls and peanut hulls will increase the crude fiber value on the label but they are poorly digested by the horse and thus the horse will not gain the same benefit.

In general, its preferable that 50% of the horse’s daily forage amount comes from long stemmed hay. Long stemmed forage provides the horse with much needed chew time. Chew time not only mimics the natural feeding behavior of the horse but it also ensures adequate saliva is produced (horses only produce saliva when they chew unlike humans). Salvia helps to lubricate food swallowed and also helps to buffer the stomach acid. The more the horse chews the more saliva is produced and the more acid can be buffered which is ideal for those struggling with gastric ulcers.

Short stemmed and processed fiber feeds take less time to chew which can lead to boredom and stereotypical behaviors.

However, you may be able ti reduce the risk of these issues by:

Although research is still lacking it is thought that long stemmed hay can stimulate the hindgut better than short stemmed hay helping to reduce the risk of colic. Therefore, when selecting a forage alternative it's best to choose one with long coarsely chopped hay rather than fine powders and combining it with some longer stemmed roughage.

Examples of quids on the floor of a stall.

However, there are situations where long stemmed forage just cannot be utilized. For example, horses with loose, damaged or lost teeth could mean that the horse struggles to chew long stemmed forage such as hay. This is often characterized by “quidding” whereby food is continually dropped from the mouth.

It may be thought that chaffs are the most ideal in these situations as they closely resemble hay but for horses without teeth, cubes and pellets are often easier. This is due to the fact that the fiber length in these are smaller and easier to consume. They also lend themselves to soaking so that the horse can simply slurp it up and swallow. As these horses tend to be unable to consume much grazing (even though they may have their head down nonstop) generally they won’t be gaining much nutritional benefit or consuming as much as you may think. Due to this the water content of their diet can be reduced and so soaking also helps to supply more water.

Horses with issues such as COPD may not be able to consume hay due to its higher levels of dust and spores which can greatly effect such conditions. Steamers are a great option here as they significantly reduce levels of dust and small particles however, they can be expensive and so fiber alternatives can be a great option as they are typically less dusty.

It’s common in the high-performance horse that appetites for larger volume ingredients such as hay dwindle during competitions, and some horses when they are away may also not consume the amount of hay they do at home. Race horses that are fed larger amounts of concentrates may not consume enough hay to ensure an adequate fiber intake. Thus, a forage alternative such as a pellet, cube or beet product may be an ideal way of ensuring adequate fiber intake for the performance horse. Beet products are particularly useful as they can help to add additional water into the diet, ensuring adequate hydration but also since they are a super fiber, they contain more fiber per pound. Meaning that you can feed smaller amounts but get more out which is perfect for horses with small appetites. The other advantage is that they are higher in energy/calories making them ideal for horses that struggle with weight gain as well as performance horses susceptible to conditions such as Tying up or Gastric ulcers. The higher energy/calorie value means that you can replace some or all grain from the diet helping keep conditions at bay without effecting performance or condition. They are also easier and more convenient to transport and store making them ideal for the sports horse.

Soaked beet pulp.

When selecting a forage alternative, you may find you need to look for different options based on the condition of the horse. For bad doers looking at fiber sources that contain alfalfa and/or beet products can be helpful as they will provide more calories per pound compared to traditional hays.

Also look for products that contain additional oils as these too will provide more calories to assist in weight gain.

For "good doers/easy keepers" look at perhaps replacing a portion of the forage ration with straw. This can help to keep chew time up whilst lowering calories. Keep in mind that good quality straw must be sourced and avoid this option should your horse struggle with issues such as colic.

Check labels and ensure you choose a product low in calories. Be careful not to assume that low starch/sugar products are also low in calories as often this is not the case as these products will often contain additional oils to replace the starch portion. Forage alternatives such as pellets are quite digestible due to their particle size and you may also find that the quality of hay used is higher than what you would normally feed and thus this could lead to good doers putting on weight, so in the case of the good doer replacing the full amount of forage with a replacer may not be possible.

If you are using a forage alterative as an addition to hay and concentrates, then it’s not vital that the alterative contains a vitamin and mineral pack and could be advantageous in avoiding over fortification. However, if you are feeding it as the sole forage source and/or without additional concentrates, look for one that is fortified or at least consider adding in a balancer to ensure your horse is covered in terms of daily essentials.

When assessing the horses forage intake be sure to weigh everything you feed. Not only will this ensure you are feeding the correct amount but help you to save costs in the long run by reducing issues of over or under feeding. Always feed by weight and not volume, for example a scoop of hay cubes may weigh 2-3lbs, but the same scoop filled with chaff may only hold 1-1.5lbs.

When looking at adding anything new into the diet it’s always worth having the diet assessed by a professional to ensure that everything in the diet remains balanced. Clarity Equine can assist you with this and offer a variety of competitive packages to suit your needs. Contact us at support@clarityequine.com for further info on how we can help you.

With winter finally upon us loss of weight is often a concern for many owners. Increased energy demands as a result of cold weather and the reduced nutritional value of pastures generally means horses may need more feed (this includes hay, grazing and concentrate feed) during winter than in summer in order to maintain body condition. Generally, we aim to have our horses’ winter ready prior to cold spells arriving however all is not lost and we can still make changes during the winter to try and prevent further condition changes.

With winter finally upon us loss of weight is often a concern for many owners. Increased energy demands as a result of cold weather and the reduced nutritional value of pastures generally means horses may need more feed (this includes hay, grazing and concentrate feed) during winter than in summer in order to maintain body condition. Generally, we aim to have our horses’ winter ready prior to cold spells arriving however all is not lost and we can still make changes during the winter to try and prevent further condition changes.

How do horses keep warm?

Horses are warm blooded animals and therefore try to keep their core temperature as close to a constant 101 ˚F as possible. To keep their temperature constant the horse will use various methods to thermoregulate and maintain this constant internal temperature no matter the surrounding environment. In the winter this may be through one of the following:

How do I know if my horse needs extra calories?

All these processes require energy (calories) in order to work and so it makes sense that the diet will need to be closely looked at.

When looking at the horse’s diet in winter we need to consider what the horses Lower Critical temperature (when the horse would start to feel cold) would be. Studies have shown that for the average healthy horse the lower critical temperature (LCT) would be around 32°F to 40°F.

Research has shown that LCT can vary both within a breed and even between different breeds. For example, it has been indicated that pony breeds have a LCT of 34.5°F to 51.44°F but for Thoroughbreds the range is 28.22 to 46.22˚F and 25.88 to 45.32˚F for Warmbloods (Marlin, 2018). This might come as a surprise but it’s much easier to lose heat when your body size is small (larger relative surface area) and harder when the body size is larger so small animals have the advantage in warmer climates and big horses in colder ones. However, don’t forget that all types of horses can adapt to various ranges overtime but in general this theory applies.

Critical temperature can also vary depending upon the horse’s condition, age and if it is adapted to colder temperatures or not. Mature horses that are unclipped, have a thick coat and are accustomed to cold climates may have a critical temperature of as low as 5˚F. It’s also been seen that LCT may even change during the winter period itself once the horse becomes accustomed to the colder temperatures.

These critical temperatures are important as horses require a total feed increase in order to provide more energy/calories to produce the extra heat required as the temperature falls below these LCT. But how do you determine what your horse’s LCT is?

This may come from experience of your horse, for example does he normally keep condition well in winter despite cold temps in your area, then your horse’s LCT may be on the lower end of the scale. However, if your horse is new to you, or you recently moved to a new area then you may need to use the above average figures as a starting point and monitor over winter.

How many more calories does my horse need?

It’s thought that 15-20% more calories per day will be needed for every 10 ˚F below the LCT. So, for a 1100lb horse needing 16Mcal per day this would increase by 2.4-3.4Mcal per day. This would equate to around 2-3pounds of good quality hay per day for every 10 ˚F the temperature drops below 32 ˚F.

This amount would obviously keep on changing as the weather does and so it’s not uncommon to start with feeding a few pounds more at the start of winter and by the end you have increased it substantially. The average horse needs 1.5% of body weight in forage dry matter per day, in winter this total could increase to closer to 2-2.5% of body weight per day.

It might be tempting to simply increase the daily concentrate intake because it is the easiest way to add more calories. However, as the general concern in winter is ensuring the horse is provided with added calories to maintain temperatures (stay warm) providing a diet high in fiber is a good way to do that.

It might be tempting to simply increase the daily concentrate intake because it is the easiest way to add more calories. However, as the general concern in winter is ensuring the horse is provided with added calories to maintain temperatures (stay warm) providing a diet high in fiber is a good way to do that.

Forages such as hay require microbial fermentation in the hindgut to maximize their use in the digestive tract. This isn’t a completely efficient process, and fermentation results in energy being lost as heat. This heat helps your horse to stay warm, so rather than increasing concentrate feed we should always look at providing more roughage first to help horses in the winter months.

Added (over and above their normal amount) roughage will also provide additional energy/calories, with the added benefit of being healthier for the gut. If possible, look for more immature hay (characterized by soft stems and a larger portion of leaf matter) rather than overly mature (very stalky with little leaf) as this provides better nutritional value. This is important during the winter as winter forage often has a reduced quality which means more hay would need to be provided than in summer to ensure the same calorie value, so factor that in when purchasing.

Immature, leafy, hay, also has a water-holding capacity that more mature hay does not have. Impaction colic can be more common in winter when horses often drink less because of cold water that is not palatable or even water that is frozen and so this can help combat this. Also, if your horse is used to a predominately fresh forage diet (i.e. only grass) then normally he will be receiving more water from his forage. Changing to a predominantly conserved forage diet (hay) drastically alters this hydration status and so introduce forage slowly to reduce the risk of impaction colics. Salt is not only for the summer months and adding salt to the diet can also encourage more drinking during this time of year. One tablespoon per 500 lbs of body weight is a good rule of thumb for salt consumption year round.

For some (older, younger, poor doers) they may need more energy than can be provided from additional hay alone and so changes to concentrates may also need to be considered alongside additional forage. Horses that experience an increase/decrease in workload in winter may also need to have their energy levels adjusted also.

How do I add extra calories?

Adding extra energy/calories can be done in several ways:

For horses looking at a reduction in workload during winter, changes to the diet may also need to be considered and may be as simple as a slight reduction in concentrate feed. If the horse is a “good doer” and going from hard to no work, it may be time to decrease concentrates or remove completely and replace with a balancer type product to ensure that the daily essentials are still provided without the calories. For pooer doers who will be working less, reducing concentrates while increasing forage through the use of either more hay or perhaps a forage extender such as beet pulp is an ideal way to keep the calories while reducing hard feed.

For horses looking at a reduction in workload during winter, changes to the diet may also need to be considered and may be as simple as a slight reduction in concentrate feed. If the horse is a “good doer” and going from hard to no work, it may be time to decrease concentrates or remove completely and replace with a balancer type product to ensure that the daily essentials are still provided without the calories. For pooer doers who will be working less, reducing concentrates while increasing forage through the use of either more hay or perhaps a forage extender such as beet pulp is an ideal way to keep the calories while reducing hard feed.

For some, winter can be a great opportunity for weight loss as keeping warm uses extra energy and thus energy expenditure will be greater than what is consumed leading to a reduction in weight. So, keep that in mind for overweight horses when looking at diet changes.

Another great tool to have on hand for winter months is a forage extender. These are designed to replace a portion/or be used in addition to the horse’s daily forage in times when hay or grazing may be of poorer quality or not as available. Keeping some on hand is useful in case hay stocks run lower than expected due to storms or unusual drops in temperatures where you feed more than you planned to. Forage extenders are available in many forms such as super fibers (soy hulls and beet pulp) or conserved grass options such as hay pellets, chaffs and cubes.

Should I blanket my horse?

A common question from many owners’ is should I blanket my horse? The answer to this is possibly not. Here are some factors which may affect this decision.

WEATHER- the coldest condition for any horse would be low air temperature combined with strong winds and rain as the colder the air temp the bigger the difference between the horses’ skin/coat temp and the air, thus the faster heat moves from hot to cold. Add in wind, and heat is lost even quicker especially if the horse is wet. Therefore, if this is a concern in your area blanketing may be an advantage.

AGE- generally older and younger horses will not cope with colder temperatures as well as the average adult horse. Generally younger horses are smaller and have less body fat and older horses may be less efficient at controlling their body temperature, may have health problems and/or have less body fat. However much younger horses may also not be used to being blanketed and so keep this in mind.

COAT- clearly coat will play a big factor in the horse’s ability to retain heat, and whether a horse has a thick coat, hasn’t grown one yet or has been clipped should be considered before deciding on a blanket. Those that are clipped are going to need more help than those that have a thick coat.

COAT- clearly coat will play a big factor in the horse’s ability to retain heat, and whether a horse has a thick coat, hasn’t grown one yet or has been clipped should be considered before deciding on a blanket. Those that are clipped are going to need more help than those that have a thick coat.

SHELTER- obviously shelter plays an important role in horses needing additional help with keeping warm. If your horse has adequate shelter this may negate the need for heavy blankets.

Additional points to consider when blanketing:

BLANKETING GUIDELINES

| Outside Temperature | Unclipped Horses- blanket needs | Clipped Horses- blanket needs |

| 40˚F to 30 ˚F | None or lightweight (older, younger, poor doers) | Lightweight- med weight |

| 30 ˚F to 20 ˚F | None or lightweight-midweight | Heavyweight |

| 20 ˚F to 10 ˚F | Midweight to heavyweight | Heavyweight plus liner |

| Below 10 ˚F | Heavyweight | Heavyweight, plus a liner and neck cover |

If you have concerns or questions about how to ensure your horse goes through the winter maintaining weight reach out for a consultation. We would love to help.

Research information taken from Dr David Marlin 2018, https://www.facebook.com/233421046862124/posts/917577288446493

Whether you are travelling south for the winter to escape the cold or for competitions, travelling long distance can be stressful for the horse. Careful management and dietary adjustments can ensure that your horse arrives in peak condition.

Horses are often transported far and wide around the country, some manage this with no issues while others struggle with stress, weight loss and fatigue.

Weight loss during transport is a common problem for horses and some can lose an average of 4.4 pounds of body weight per hour (Marlin, et al 2002). A large proportion of this is due to loss of water and therefore for transportation of over an hour adequate water must always be provided or provided at an adequate number of stops. Dehydration can not only increase the risk of impaction colic but can also lead to early fatigue and thus poor performance on arrival.

Providing soaked hay can be one way of incorporating a little more water during long trips which can be useful if your horse is fussy about drinking away from home. It also has the advantage of cutting down on dust particles within the confined space which can have an impact on respiratory health.

Water sources can have a difference in taste and smell due to the various amounts and types of dissolved solids it contains. This can reduce your horse’s overall water consumption when away from home. Adding a flavoring (such as pure apple juice) to your horse’s water prior to travel, and then repeating when away from home, allows your horse to become accustomed to a familiar taste that doesn’t change and helps to mask any difference in smell or taste. However always ensure that both flavored, and plain water is offered.

Another way to ensure your horse stays hydrated is to add salt into the diet, as salt stimulates the thirst mechanism and the need to drink. 1 tablespoon per 500 pounds of body weight per day is generally recommended as horses rarely consume enough from a salt block.

Whilst most weight loss can be attributed to water loss have you ever thought of the amount of energy horses use whilst being transported?

Numerous studies on the subject, which included trailers and bigger horse boxes/floats, estimated that the amount of energy a horse uses during transport is in the region of an equivalent amount of walking. Therefore, 1 hours worth of travel could equal approximately 1 hour of extra walking. The implication of this is that transport is tiring for horses and thus expecting your horse to travel long distances and then compete is not ideal for performance.

Numerous studies on the subject, which included trailers and bigger horse boxes/floats, estimated that the amount of energy a horse uses during transport is in the region of an equivalent amount of walking. Therefore, 1 hours worth of travel could equal approximately 1 hour of extra walking. The implication of this is that transport is tiring for horses and thus expecting your horse to travel long distances and then compete is not ideal for performance.

So, does this effect the diet? In short yes, if the horse uses more energy than he is eating then weight loss is likely to be seen. Therefore, it’s worth factoring in how much extra energy the horse is going to need in order to cover his transport time.

Although every horse is different and fitter horses may use less energy, it’s thought that roughly one hours’ worth of walking would use in the region of 956 to 1,434kcal of energy for an average 1100-pound horse. Thus, if travelling is the equivalent of walking, then each hour of travel would use roughly 0.956 to 1.434 Mcal energy. This could be increased further if there is any thermal stress (extreme heat for example) involved. Some studies have revealed that travelling in a trailer uses more energy than travelling in a larger float/horsebox. However, using the energy ranges above as an estimate of what needs to be replaced, no matter the mode of transport, gives peace of mind that your horse is well covered.

As an example, if you travel for 4 hours prior to a show that’s around 3.8 to 5.7 Mcal of extra energy your horse may need to be provided with.

That is the equivalent of around:

7.2 pounds of extra good quality grass hay

5.8 pounds of good alfalfa

3.3 pounds of a concentrate feed (at an energy level of 1700mcal per lb)

5.4 pounds of a beet pulp

All changes to the diet should be done gradually but if you are simply providing more of a feed/hay that the horse already receives then you don’t have to make changes too far in advance and you can simply increase the amount.

If you are adding in an extra product that the horse doesn’t normally receive then do so ahead of time (at least 7-10 days) to allow the horse’s digestive system to adapt to the new changes without putting his digestive system at risk of any upsets. Should you be changing your horses feed on arrival, plan to take enough of his previous feed in order to make that change over slowly. Always ensure when packing for your trip that you calculate the amount of food your horse will need so that you don’t run short.

Should you travel out of state often, changing your food to a national brand has the added advantage of being available across the country. But be aware that feed manufactured in different mills can differ as ingredients, milling techniques and climate changes can alter the composition of a product, so speak with your manufacturer prior to selecting a feed so you know what to expect.

Ideally no horse should go any longer than 4 hours, during transport or competition, without something to eat, as this can increase the risk of colic or gastric ulcers. Saliva is a fantastic gastric acid buffer; however, horses only produce saliva when they chew. Thus, keeping them eating/chewing will ensure your horse has an extra added level of protection. Simply providing extra hay ad lib, will allow your horse to keep his digestive system healthy as well as simulating natural grazing behaviours. When travelling, consider the use of Alfalfa which also has an acid buffering capacity and can further help in reducing the risk of gastric ulcers.

Ideally no horse should go any longer than 4 hours, during transport or competition, without something to eat, as this can increase the risk of colic or gastric ulcers. Saliva is a fantastic gastric acid buffer; however, horses only produce saliva when they chew. Thus, keeping them eating/chewing will ensure your horse has an extra added level of protection. Simply providing extra hay ad lib, will allow your horse to keep his digestive system healthy as well as simulating natural grazing behaviours. When travelling, consider the use of Alfalfa which also has an acid buffering capacity and can further help in reducing the risk of gastric ulcers.

Keeping in mind that travel is costly to your horse’s energy levels, and can place undue stress on the horse, adjusting his diet and management routine can go a long way to ensure that your horse arrives still with plenty of fuel in his tank, as well as maintaining his condition.

Marlin, D, Nankervis, K (2002) Equine Exercise Physiology p277.

As we head into the Halloween weekend it may have got you thinking about what seasonal treats you can prepare for your horse. Many owners often ask if its ok to feed pumpkin and the simple answer to that is yes, the traditional orange pumpkin available throughout the fall is suitable. Butternut, zucchini and acorn squash are also nontoxic to horses.

As we head into the Halloween weekend it may have got you thinking about what seasonal treats you can prepare for your horse. Many owners often ask if its ok to feed pumpkin and the simple answer to that is yes, the traditional orange pumpkin available throughout the fall is suitable. Butternut, zucchini and acorn squash are also nontoxic to horses.

However be careful not to generalize all types of gourds, as green, yellow, white, striped, bumpy and smooth gourds can be potentially toxic and can lead to colic, diarrheas and gastrointestinal irritation.

The one thing to look at with any treat given, is what is the nutritional value of that feed item to the horse and could there be an issue?

The first area many people automatically consider is that of sugar content.

Pumpkin has around 1.7g per 100g as fed. If we consider this against other feed items such as carrots which have 7.4g per 100g and even grass which could have around 10g per 100g. Pumpkin therefore comes in fairly low.

The total NSC value (which is the sum of starch and sugars (water soluble carbohydrates)) of pumpkin comes in at around 10%, making it suitable for horses with conditions such as Equine Metabolic Syndrome, PSSM, Laminitis, Cushings etc. Its overall calorie content is also fairly low and therefore it can be useful in situations where calories are being monitored. However if your horse is on a calorie controlled diet, remember moderation is key and all the little treats add up over time so make sure you account for this when feeding.

One area of caution with pumpkin is that it provides 0.4g of potassium per cup. If we compare this to grass hays which provide around 8.5g per pound, this small amount per measured serving for the average horse, is nothing to be concerned about. However if you have a horse with HYPP (Hyperkalemic Periodic Paralysis), where limiting potassium intake is necessary, it might be wise to give the pumpkin a miss.

When preparing your pumpkin, fresh is always best. Don’t use pumpkins that have been decorated, have had candles in them or those that have been soaked/washed in solutions to make them last longer on the front porch and certainly not ones that have started to soften or rot.

Cutting the pumpkin into pieces can be useful for horses with poor teeth, whereas the average horse can probably cope with having the pumpkin put into the stall or field whole. Although ensure that the stem is removed as this can pose a choking hazard. Alternatively you could also cook and puree the pumpkin to add to your horses feed. Canned pumpkin can also be used but check the label and choose one that contains no additives, sugar or salt.

Pumpkin seeds can also be included and in actual fact they have some interesting properties. One study (Grzybek, et al 2016) looked into the use of pumpkin seed extracts in mice to control round worms and found significant decrease in fecal egg count worm burdens. However, there is no research in horses to show that pumpkin seeds can be used in place of dewormers.

Pumpkin seeds also supply nitric oxide. Nitric oxide exists as a relatively short lived gas in the body, and is manufactured using the amino acid, arginine. It has many important roles such as helping to keep blood vessels dilated and blood flowing smoothly, learning and memory, it assists in the release of insulin from the pancreas, is involved in ovulation and even the ability to smell.

Pumpkin seeds also supply nitric oxide. Nitric oxide exists as a relatively short lived gas in the body, and is manufactured using the amino acid, arginine. It has many important roles such as helping to keep blood vessels dilated and blood flowing smoothly, learning and memory, it assists in the release of insulin from the pancreas, is involved in ovulation and even the ability to smell.

Pumpkin seeds are higher in calories from fat (12g of fat per cup) with a higher level of Omega 6 fatty acids. Therefore larger amounts would not be suitable for all horses.

Remember introducing anything suddenly should be done with caution and so stick to feeding small amounts, around a small cup a day, to ensure your treat doesn’t turn into a trick!

For many, winter means darker days, more blankets, mud and much longer coats. It therefore may seem counterproductive thinking about your horse’s coat condition prior to spring. However, now is the best time, as good practices started early will allow for adaptations to take place for sparkling spring coats.

For many, winter means darker days, more blankets, mud and much longer coats. It therefore may seem counterproductive thinking about your horse’s coat condition prior to spring. However, now is the best time, as good practices started early will allow for adaptations to take place for sparkling spring coats.

If you are concerned with your horse’s coat condition it may be worth a quick check with your veterinarian to rule out conditions that could affect the coat, such as gastric ulcers, internal parasites, and even Cushing’s disease.

While nutrition plays a part in horses having good quality coats there is more to it than that. As with all coat colors, dapples and coat condition in part, are controlled by genetics. Some breeds just simply develop a much thicker, longer, “scruffier” coat than others. Dapples themselves result from variation in the patterns of red vs. black pigment along the hair shaft, rather than changes in pigmentation across the skin. Therefore, they do disappear when you clip a dappled horse. Do keep in mind that some horses are just more likely to shine than others.

Even horses in good condition could be missing the essentials needed to support a shiny coat. Nutrients, such as omega fatty acids; trace minerals such as zinc and copper; essential amino acids and vitamins such as A, E, B must be present in the correct amounts to get a great coat.

Vitamins and Minerals

The best place to start is with your forage. Feed the best-quality forage you can, and make sure your horse is getting enough.

Vitamin A is a vital nutrient in the role of skin health, and while equine deficiencies are rare, they can occur if older hay is fed. Beta-Carotene is the precursor to vitamin A and is abundant in fresh forages. However, it is lost at a rate of 10% per month from hay. Therefore, by late winter/early spring hay may have lost 50% of its beta-carotene, and by the time hay is a year old it’s likely horses will need additional support to meet basic daily requirements.

Fresh good-quality grass pasture is also an excellent source of vitamin E. Diets lacking in Vit E can be a causative factor in dry skin, skin infections and allergic reactions.

A horse that is sustaining itself on good-quality grass pasture will be consuming significant amounts, however, because vitamin E is not heat-stable its levels in hay can decrease over time. Another consideration is that in winter months when fresh grass isn’t as plentiful the amount consumed per day will be less than in summer.

Both, Vit B7 (Biotin)which is necessary for skin health, and B6 which is a valuable component of protein metabolism, should also be noted for coat condition. A deficiency can be seen sometimes in older horses which results in thinning of the coat, bald patches and extremely dry skin and scaling.

Zinc and copper are two trace minerals that are worth paying attention to. Both are needed for melanin production, and so have an impact on coat color. If the hair contains inadequate amounts of melanin, it is unable to resist damage from ultraviolet light which can lead to damage and fading. Copper is also needed by the enzyme lysyl oxidase, which is necessary for the maintenance of the cross-bridges in collagen within skin. Without adequate copper these cross linkages are weakened, and the skin loses structural integrity.

Fatty Acids

Fats supply essential fatty acids (EFAs) which are a component of skin oils (sebum) that coat both the skin and hair shaft. The hair shaft is covered in cells that help to retain moisture. When there is a good coating of sebum these cells lay flat, giving off a good reflection which we perceive as shine. However, if damaged, moisture is lost from the hair shaft, and the hair becomes dry and these cells in a sense “stick up” and no longer reflect light with the same luster. Diets that don’t provide adequate amounts of EFAs could result in a dry coat that’s more prone to damage and a dull appearance.

Fats supply essential fatty acids (EFAs) which are a component of skin oils (sebum) that coat both the skin and hair shaft. The hair shaft is covered in cells that help to retain moisture. When there is a good coating of sebum these cells lay flat, giving off a good reflection which we perceive as shine. However, if damaged, moisture is lost from the hair shaft, and the hair becomes dry and these cells in a sense “stick up” and no longer reflect light with the same luster. Diets that don’t provide adequate amounts of EFAs could result in a dry coat that’s more prone to damage and a dull appearance.

Do take caution before adding fat as it may not be appropriate for all horses based on body condition. However, even fairly small amounts of fat should have a positive impact on coat quality without contributing too many calories.

Try to use fat sources that supply larger amounts of Omega-3 than Omega-6, as Omega 3 has anti-inflammatory properties which have been shown to have positive effects on skin quality and aid in the reduction of itching. Fish oils and flax are good Omega 3 options.

For coat condition 2 to 4 ounces per day for an average-sized horse would be ideal.

Dietary fats are also beneficial as they facilitate the absorption of fat-soluble vitamins A, D, E, and K.

Protein

Hair is 90% protein and the hair shafts are made up of the protein keratin. Diets that provide inadequate amounts of protein or that lack essential amino acids (EAA) could result in poor hair growth. In modern diets generally its not a lack of protein that is an issue but a lack of EAA’s such as lysine. A simple way to improve the EAA level is to include a variety of hays including alfalfa and/or use an appropriate concentrate or ration balancer to ensure levels are met.

Hair is 90% protein and the hair shafts are made up of the protein keratin. Diets that provide inadequate amounts of protein or that lack essential amino acids (EAA) could result in poor hair growth. In modern diets generally its not a lack of protein that is an issue but a lack of EAA’s such as lysine. A simple way to improve the EAA level is to include a variety of hays including alfalfa and/or use an appropriate concentrate or ration balancer to ensure levels are met.

Besides diet, good grooming practices are vitally important for coat quality.

Professional groom Liv Gude, founder of Pro Equine Grooms, notes that “It boils down to environment, care, health, and diet. Your horse’s coat shows a little bit of what’s going on inside him, as well as just how dirty he likes to be on the outside. Daily currying and brushing is more than removing dirt, it’s skin care. Sebum, the natural oil produced by the skin, is antimicrobial, water-proof, and shiny. Your grooming skills are needed to maximize the benefits of healthy skin.”

To improve a horses coat “Get on board with spending a ton of time on curry combing. Grooming gloves are great for this, you can use two hands at once and really get down to it” suggests Gude, once done dirt can be removed with a stiff brush.

As we head towards winter the question many ask is, “Should I clip my horse or not”?

“There are plenty of reasons why you would need, or not need, to clip your horse”, says Gude. “Part of this is a personal preference. But, the largest and most important reason is to shorten your horse's coat for health and comfort”

“While it's commonly thought that climate and temperature dictate how much hair a horse will grow, it's actually the amount of daylight.” “The climate around you may not match what your horse grows! Clipping is a thoughtful way to help him stay comfortable”

Liv Gude also notes that “when an exercise or training routine over winter creates a lot of sweat your horse may need help thermoregulating efficiently”

“One study discovered that clipped horses maintained their vitals well, while unclipped horses had longer exercise recovery rates. Another found that clipped horses showed less strain on the body's activity to thermoregulate and exercise more efficiently. A sweaty horse in winter also has to deal with a longer drying time”

“If there's a history of skin infections, like equine pastern dermatitis (EPD), rain rot, matted hair, sores, or other weird skin funk, you may want to consider clipping. Long hair on some horses is the perfect storm for a skin issue. Hair traps moisture, dirt, sweat, dander, mud, and sometimes even lice and mites. You can see the skin, clean the skin, and medicate it much more comfortably without a forest of hair. It's just that simple”

If you decide that clipping is for you this winter, check out Liv’s extensive guide to clipping. Whether you decide to clip or not, feeding the necessary precursors for a healthy coat through the winter months will give you the best chance of a beautiful shiny horse come spring.

Not sure if your horse is getting all these key coat nutrients in the correct amounts? We would love to help.

For everything you need to know about clipping your horse check out Liv's guide here.

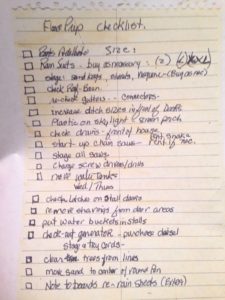

As summer starts to fade and the beauty of fall emerges now is a good time to carry out some fall health and management checks to help prepare for the winter months.

As summer starts to fade and the beauty of fall emerges now is a good time to carry out some fall health and management checks to help prepare for the winter months.

VACCINATIONS: fall vaccinations will depend largely on location and horse’s risk level, so discuss options with your veterinarian to ensure your horse is properly covered.

PARASITE CONTROL: as grasses get shorter in fall, parasite loads tend to increase as horses graze closer to manure and this places even more importance on parasite control including deworming. Fecal egg counts are suggested to provide a program that works for your situation and geographical area as well as reducing the risk of drug resistant parasites.

DENTAL CHECKS: a yearly dental check is recommended for all horses and fall is a great time to do this, to ensure that going into winter your horse can chew correctly and thus make the most of his diet in order to sustain body condition over winter. Older horses and those with teeth issues may need more regular check ups

EVALUATE YOUR HORSES CONDITION: Asses your horses body condition so you can make changes before winter arrives. For horses that are underweight additional calories will need to be added for weight gain, this can be done in the form of higher calorie concentrates, higher calorie grasses such as Alfalfa, added fats and oils, or super fibers, such a beetpulp products which provide calories without excessive amounts of starch or sugar. Speak to a nutritionist to ensure the right option is selected for your horse.

For those that are overweight fall and winter can be a good time to help your horse drop. However, consider using a balancer to ensure all the daily essentials are provided without the calories, as even good hay and grazing can be deficient in nutrients.

PASTURE CONDITIONS: This can be largely dependent on your area, as for some, fall signifies the dwindling of grass growth while for others an increase in rainfall produces a flush of new grass before winter sets in.

In areas where grass is sparse consider introducing more hay to your horses in both their stall and paddock. When grazing is not as available horses tend to indulge in vegetation which may not be suitable and could lead to poisonings thus providing extra hay can help avoid this. Additional hay also helps to support the drop in nutritional value of pasture during winter months.

Pasture has a much higher water content than hay and so by adding more hay, water intake is reduced. Giving the horse time to change over slowly to a higher forage-based diet will give them time to alter their drinking habits in order to consume more and help reduce the risk of impaction colic. Including 1 tablespoon of salt per 500lbs of body weight is a good guide to stick to as including sodium helps to stimulate thirst and ensures your horse consumes enough water.

Research has shown that tepid water is drunk in much higher volumes and so when temperatures drop ensure your horses water is at a more tepid temperature to ensure they drink enough.

Calculate and ensure you have adequate supplies of hay as stocking up will not only help you avoid the higher winter prices but ensure you have enough to last you through the winter months. Horses should receive at least 1.5% of body weight per day in additional roughage. However, you may end up needing more to sustain your horses body weight in winter and so estimating on 2% of body weight per day per horse would give you a more accurate reflection of how much you need to buy. Due to drought and fires in many areas hay supply this year could run low and so if you feel this may be a concern think about adding additional roughage support to the diet by using chopped hay, hay cubes/pellets and or beet products. Ensure your storage area is pest free and protected from the elements to guarantee your hays longevity.

BEWARE OF LAMINITIS: For those living in areas where rains return in fall causing a flush of grass growth be aware that this grass flush can be as risky as spring grass for horses at risk from laminitis. Pasture grasses contain high levels of soluble sugars and NSCs during their active growth phase. When cold temperatures cause growth to cease, the sugar cannot be utilized as fast as it is produced and thus it accumulates in the plant in an attempt to fuel regrowth. For horses prone to laminitis, restrict or avoid grazing when night temperatures are below 40F, followed by sunny days as the colder nights will prevent the plant from using its sugars leading to higher levels of NSC in the day.

For all horses there is a seasonal increase of the hormone ACTH from mid-August through November. This rise is related to changes in hormone activity ultimately responsible for winter coat growth. However, in horses with Cushings (or undetected Cushings) this seasonal ACTH rise generates levels much higher than normal. This is a concern as ACTH stimulates the adrenal gland to produce cortisol and long-term elevated cortisol puts vulnerable horses at high risk for fall laminitis and/or insulin resistance. Its therefore advisable to test your older horse for Cushings during this time in order to avoid long term issues.

MATCH DIET TO EXERCISE: Ensure that your horses diet matches this workload. Horses may experience a drop in exercise in fall and winter and so the diet would need to be matched to ensure excessive weight gain and/or behavioural changes are not seen. For those still in work and performing regularly make sure your diet accounts for the drop in nutritional value of pasture and that additional supplementation is provided if necessary.

DO SOME HOUSEKEEPING: Address anything that needs fixing. Repairs ignored now will become much bigger problems once winter is in full swing. In cold areas ensure your pipes are insulted enough to avoid freezing and even have your barn checked for structural integrity to ensure it can withstand heavy snow falls. Assess areas of your pasture and yard that are known to become muddy and either ensure that the water run-off is adequate or place a covering (such as wood chips or a commercial pad or panel) to help manage mud in these areas. Check light fittings work and that you have enough for those darker days. Now is also the time to check blankets and ensure they fit correctly, are clean and ready to use.

If you have any concerns about your horse’s diet or condition this autumn do not hesitate to reach out. We are here to help!

Competition season is upon us which means transporting your horses long distances to shows. As tough as trailering can be on horses, there are a few things you can do to make their time in the little box more enjoyable.

transporting your horses long distances to shows. As tough as trailering can be on horses, there are a few things you can do to make their time in the little box more enjoyable.

Preparation

Wrapping your horse for travel can be a good way to protect his or her legs in the trailer. Shipping boots and standing wraps are two ways to do that, as long as they are used properly. You should make sure that the shipping boots fit your horse well, since they tend to not be available in sizes as variable as standing wraps. Standing wraps need to be done properly, otherwise they may do more harm than good. When wrapping, start at the front of the cannon bone and wrap towards the back of the horse, making sure all layers lie flat against the leg so that no pressure points are created. It’s important to wrap tightly enough so that they don’t slide down, but not too tight as this can cut off blood supply and damage the tendons. You should be able to fit 1-2 fingers inside the wrap. Using thick enough padding under your standing wraps is key to insuring correct wrap tension as this allows you to put enough tension on the wrap while at the same time not transferring excessive tension to the leg.

If you are trailering when it’s hot out, you should be aware that using shipping boots and wraps will hold in heat around your horse’s legs, which can be bad for tendons. Heat can increase swelling and fatigue of tendons, raising risk of injury. The decision to use either can sometimes be a calculated risk assessment. Bell boots can be used with standing wraps or alone but again may rub on long journeys especially in warm weather.

Hydration

Trailering is quite stressful on a horse’s body. Their muscles are constantly working to maintain balance for the duration of the trip, causing them to lose a fair amount of sweat and become dehydrated. We tend to not notice this as air movement in the trailer, especially if the windows are open, provide a breeze to dry their sweat. Dehydration and electrolyte loss from sweating can also cause fatigue, decreased function of nerves and muscles, alkalosis, and more. This can greatly affect performance, so if you’re travelling to a competition this may be especially important. In order to avoid dehydration from hauling, preventative measures should be taken in the days leading up to the trip. Electrolytes can be given in addition to daily salt either via grain or mixed in their water, in order to encourage your horse to drink more water and stay hydrated. Starting your trip with a well-hydrated horse will make a difference! Make sure your electrolytes are at least 60% salt, as sodium is the most important part of restoring ion balance. After trailering, be sure to offer your horse plenty of water and give more electrolytes if they aren’t interested in drinking. Always make sure that your horse has access to plain water if placing electrolytes in drinking water.

Air quality and tying your horse

Another very important consideration while trailering is your horse’s ability to breathe on the road. Firstly, if you like to provide your horse with hay on the road, consider the type and placement of your feeder. Nets are widely used as a way to keep horses busy on long hauls and have a few pros and cons. They act as slow feeders to keep a low, steady state of feed in your horse’s digestive tract thus aiding in ulcer prevention. Other alternatives like mesh corner feeders or hay bags with a small, netted opening are other options. It is important to alter these based on the height of your horse. Do not make them too low otherwise they may hang a hoof on them. Also try to avoid hanging them in such a way that the horse has no opportunity to move his head away from them. Having hay in the trailer can be a major source of dust and may cause breathing issues. This is especially true if your horse has to breath into the hay for the entire ride.

Research also illuminates interesting points about tying your horse while trailering. Untied horses choose to travel down the road hind-end first—essentially “backwards” of traditional practice. The “rear-facing horses have fewer… total impacts [with the trailer walls] and losses of balance” than those that are tied (Clark et al 1993). It is recommended that you practice this on a case-by-case basis. This method works in a stock trailer, box stall, or slant trailer with the dividers removed. Additionally, a study conducted by Stull and Rodiek 2010 found multiple compatible horses can safely travel untied, but practice this on a case-by-case basis.

Stull and Rodiek also found the levels of white blood cells and cortisol were higher in tied horses than untied horses. The number of white blood cells (often used as indicator of infection) during recovery were three times greater in tied horses than untied. This confirms the findings of many other studies linking elevated head posture to an increased number of tracheal bacteria. Horses need to lower their head for tracheal secretions to flush the area and prevent bacteria build up. Failure to do so can lead to pneumonia and other respiratory problems. If your horse frequently experiences respiratory issues after travel, you may consider loosening the lead rope (if safety permits), traveling with your horse untied, or making stops to let your horse drop his head.

Whether you are trailering for a show or a weekend trail ride, lessening the stress your horse experiences while on the road makes the trip more enjoyable for all. It is especially important to consider these tips before embarking on long hauls where horses undergo extended periods of stress and fatigue. Always hydrate and offer electrolytes post-travel. It is important to walk your horse to let them stretch their legs and assess soundness as well as to get the gastrointestinal tract moving. Happy travels!

Works Cited

Clark, Diana K., Ted H. Friend, and Gisela Dellmeier. "The Effect of Orientation during Trailer Transport on Heart Rate, Cortisol and Balance in Horses." Applied Animal Behaviour Science 38.3-4 (1993): 179-89. Web.

Stull, C. L., and A. V. Rodiek. "Effects of Cross-tying Horses during 24 H of Road Transport." Equine Veterinary Journal34.6 (2010): 550-55. Web.

Gross, W.B. and Seigel, H.S. (1983) Evaluation of the heterophil/lymphocyte ratio as a measure of stress in chickens. Avian Dis. 27, 972-979.

Every 3 months, you find yourself  staring at a shelf full of dewormers with more questions than answers. More often than not, you grab for a familiar-sounding wormer such as an ivermectin like Zimectrin®, a fenbendazole like Panacure®, or a moxidectin like Quest®. Although each of these wormers have their own purpose, few know which anthelmintic to use at what time. It turns out, this method of routine worming has inadvertently led to problems with parasite resistance

staring at a shelf full of dewormers with more questions than answers. More often than not, you grab for a familiar-sounding wormer such as an ivermectin like Zimectrin®, a fenbendazole like Panacure®, or a moxidectin like Quest®. Although each of these wormers have their own purpose, few know which anthelmintic to use at what time. It turns out, this method of routine worming has inadvertently led to problems with parasite resistance

Resistance on the Rise

Articles released by the American Association of Equine Practitioners and University of Florida’s Large Animal Clinic report startling information about the emergence of resistant parasites. Anthelmintic resistance essentially means parasites are able to survive a dose of a dewormer that will typically kill the given species. Furthermore, resistance is an inherited trait passed on to offspring (AAEP).

Around 40 years ago, veterinarians recommended regular deworming intervals as a way to control large strongyles—a very prominent parasite that posed a lot of problems at the time. The regular intervals essentially diminished the population by keeping larvae from growing into harmful adults. Now, after years of this method, the problem has shifted away from the less-prevalent large strongyles and toward other parasites (AAEP). In 2001, Kaplan, Klei et al. conducted a study to examine resistant parasites in Southern United States and found that small strongyles are creating a new threat to horses. They concluded small strongyles are showing resistance to fendendazole, oxibendazole, and pyrantel pamoate leaving only one anthelmintic drug class (avermectin/milbemycin) without resistance. This means that some horses (almost half of those in the study) only have one drug class left that will kill parasites.

Furthermore, small strongyles elsewhere in the world are showing resistance to avermectin/milbemycin (Kaplen, et al). The problem arises from horse owners today following parasite control recommendations from 40 years ago. If this continues, treatments will become less effective and give rise to greater problems.

Deworming Meets Modern Methods

Veterinarians are now recommending a new, method of parasite control that does not involve a “one size fits all” approach. They are shying away from using a routine calendar deworming schedule and now suggesting a more customized regime for a healthy and happy horse. Owners should treat their horses by targeting a specific parasite with its biology and lifecycle in mind using an affective anthelmintic to get the job done. This starts by having your veterinarian perform an FEC, a fecal egg count, to determine if your horse is in need of parasite control and if so, which kind of control. They can also test the horses to reveal which dewormers work and which dewormers do not work for your horse.

Most horses have low populations of worms at any given time. Although this makes many horse owners cringe, it is actually okay and makes for a healthy animal. Low levels of parasites stimulate immunity and very rarely cause any disease. Therefore, it is important to perform these tests regularly to know the healthy baseline for your horse and when populations need to be controlled.

The Fecal Egg Count Reduction Test (FECRT) can tell you if your horse’s strongyles or ascarids are resistant to a given dewormer (AAEP). A veterinarian performs a fecal egg count before deworming and then another fecal egg count 14 days after giving the dose. Those numbers are then used to calculate the change in parasites by using the FECRT equation. AAEP has guidelines of suggested levels of no resistance, susceptible to resistance, suspected resistance, and resistance. Your veterinarian may apply the result from the FECRT equation to these guidelines to get a better understanding of your horse’s parasites. If a horse has a higher than normal result, a veterinarian can provide you with the exact product and dosage to treat the problem efficiently and effectively.

Deworming Schedules for Different Horses

For those curious about a “typical” deworming schedule, Colorado State University and the Association for Equine Practitioners outline a few guidelines for adult horses, pregnant mares, and foals. After a vet performs a fecal egg count, they will know the eggs per gram of manure (EPG). Based on CSU’s Equine Recommended Deworming Schedule, adult horses will fall into either of three categories: Low Shedders (less than 200 eggs per gram), Moderate Shedders (between 200 and 500 eggs per gram), and High Shedders (greater than 500 eggs per gram). Your veterinarian can then determine if deworming is needed and the correct dosage. If deworming is needed, Colorado State University suggests these products and times based on the EPG from a fecal egg count:

Adult Horses

| Shedding Rate | EPG | FEC Test Time | Spring | Summer | Fall | Winter |

| Low

Shedders |

<200 | Test in spring and fall | Ivermectin

Moxidectin |

N/A | Ivermectin

Moxidectin with praziquantel |

N/A |

| Moderate Shedders | 200-500 | Test in spring and fall | Ivermectin

Moxidectin or double-dose fenbendazole for 5 days |